This post appeared in a previous blog and is here for posterity’s sake.

Interesting story from the New York Times on The Great Subway Map Wars:

One day not long ago, in a sunlit apartment on the Upper West Side, John Tauranac could be found examining a large, taped-together draft of a subway map.

[…]

The map also did something that present-day New Yorkers take for granted. It picked out parks and islands, labeled airports, and identified neighborhoods in blue type. In other words, it showed many features of aboveground New York – just as the M.T.A. map does, with its faint street grid, its bridges, train tracks and cemeteries.

Mr. Tauranac’s latest effort is also a potent reminder that one of the stormiest battles involving New York’s self-image involved neither development nor political leadership, but what would seem the most mundane of issues: the look of the city’s subway map.

This is a story about the overreach of Modernism (as in Corbusier) and how a movement became an aesthetic. The above graphic shows three phases of the New York City Subway map, from top to bottom: Unified 1939 map, Vignelli’s 1972 map, and the present-day map (pdf). I ask a simple question: which one would you like to use each and every day?

Vignelli’s 1972 map is, contrary to prevailing thought, an atrocity. The city is not a machine. Some have commented upon the design as …a marvelous conceptual map, and it was easy to read. It was a tool for navigating the subways, although not one for navigating the city streets.

I take exception to the first point, and agree with the second. Vignelli’s map is a put-on of Harry Beck’s London Tube Map which disregards London’s geography for a “rational” map. Vignelli’s map completely disregards New York’s strange historical accident of a subway system in addition to New York City’s unique geography.

Case in point: who thinks it is a good idea to have both local and express stations – the third most important piece of information after line number/letter and direction – designated by the same symbol?

This flaw is a wholly separate problem than Vignelli’s strange contortion of the landscape to fit his machine. Besides Chicago, New York City is distinctly defined by the gridiron; besides the effect on Manhattan by the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, the grid is a huge component of Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens, albeit in multiple overlays and intersections. One’s conception of New York City is hard to disengage from the geography. Michael Beirut makes exactly this point: …a lot of Manhattanites could tell you authoritatively how long it would take to walk from Fifth and 28th to Seventh and 44th. So the geographic discrepancies in the Vignelli map, which are no more than those you find in lots of subway maps around the world — they’re just glaring.

While the Unified 1939 map showing both subway and the extensive elevated lines is a charming but confusing failure at information presentation, it is more successful at its’ job than Vignelli’s map. And the current map (pdf) will not win design awards, it is a clear and concise diagram of the subway which lives inside the context of the city.

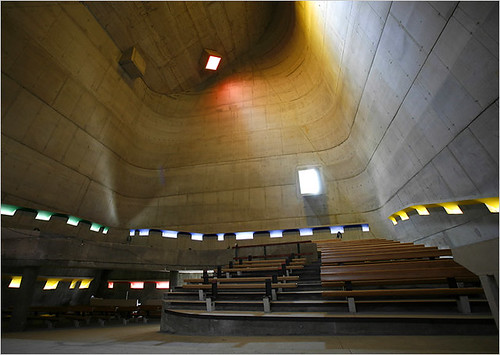

Clearly, today’s subway map is easier to use than previous maps. While not the spartan tabla rasa of Vignelli’s 1972 map, today’s map reflects reality and the city. Vignelli’s map is the repudiation of the messy life of urban living. However, life is not a geometrically pure existence, New York City even less so. By distilling and warping away the actual geography of the city and its’ connected vitality, Vignelli isolated the city from the people, much like Corbusier’s Ville Contemporaine (1922) which envisioned three million people living in high rise filing cabinets.

It is interesting that Vignelli’s turning away from the city is during the exact period when the city was dying and was told to Drop Dead. Urbanism was thought to be dead, and what purported to be Modernism was springing up all around New York: World Trade was going up on Radio Row, Lincoln Center invaded the middle class Upper West Side, and the Bronx was burning (read the excellent book).

While parts of the city have become Disney, and it is increasingly hard to survive in a city already a playground for the rich, I for one, am quite happy to not be living in Vignelli’s cubic wasteland.

For more information, check out NYC Subway’s historical map collection, a history of NYC Government Issued Maps, and compare New Jersey Transit’s map.